Poznań is where they say Poland began, back in 966 when the first king converted to Christianity here. A cathedral marks the spot, built, strangely, of red brick (doesn’t that mean industry?) – yet perhaps not so strange when you consider the building materials that must have been available in this flat riverland.

Poland ended, temporarily – long-term temporarily – when it was swallowed by its neighbours in the late 18th century; but it wasn’t like the Poles to take that lying down. After the second partition of their country in 1794, they rose up and socked it to the Russians at the battle of Racławice, commemorated in the panorama at Wrocław. The revolt was put down and a third partition wiped Poland off the map in 1795, but with a little help from Bonaparte they were up and at the Russians again in 1807. After Napoleon had messed up royally by invading Russia and then been dispatched to St. Helena, Poland was carved up once more; but the Poles let the occupying Russians have it in 1830, the Austrians in 1846, and the Russians again in 1863, with predictably disappointing results each time.

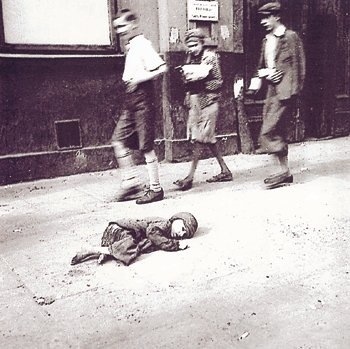

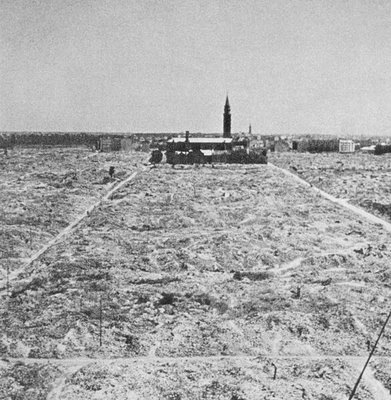

When the Russian Empire collapsed in 1917 and the new Soviet government signed Poland over to the Reich, it was the Germans’ turn; here in Poznań (which the Prussians, as Posen, considered German turf) independence was declared on December 27 1918, and followed immediately by an armed uprising. The Germans fought back in early 1919, but the issue was decided at Versailles when an independent Poland, including Poznań, was finally created. After the Second World War, with the country now in an icy Soviet grip, Poznań was the first place to rise when, in June 1956, foreshadowing the Hungarian uprising later that year, workers struck and took over the city administration. This time it lasted all of 20 hours before being ruthlessly put down, with the loss of perhaps 100 lives. Both the 1918 and 1956 risings are commemorated in small, thoughtful and (particularly the 1956 one) under-visited museums.

But it’s not just that the Poles won’t lie down; they get up and party too. I had sensed this in Wrocław, seen it in Kraków and Lublin, heard it in Warsaw, and now, with Stephen as my guide, I was doing it in Poznań. 9.30, a fine microbrewery in the main square was filling up; 10.30, a makeshift party town down by the riverbank was going strong well after the band had finished; after midnight, in a big multi-level pub back in the centre, it was scarcely possible to get a seat, with no sign of anybody going home. It seemed like everybody in Poznań under the age of 30 was out having fun. And this was Wednesday night – I wonder what the weekend is like?