Equipped with my €30 visa from the religious authorities, I took the fast boat from Ouranoupolis to Dafni, the port of Mount Athos (though that makes it sound grander than it is – there are about six buildings). Since Athos, the Holy Mountain of Orthodox Christianity, bans women, everybody on the boat and on the dock at Dafni was male (which raises interesting questions about the orientation or otherwise of all the ancillary staff – customs officials, shopkeepers, bus drivers, gatekeepers and so on who live and work on the mountain).

Equipped with my €30 visa from the religious authorities, I took the fast boat from Ouranoupolis to Dafni, the port of Mount Athos (though that makes it sound grander than it is – there are about six buildings). Since Athos, the Holy Mountain of Orthodox Christianity, bans women, everybody on the boat and on the dock at Dafni was male (which raises interesting questions about the orientation or otherwise of all the ancillary staff – customs officials, shopkeepers, bus drivers, gatekeepers and so on who live and work on the mountain).

As I was leaving the boat the sole other pilgrim (for want of a better word) on board hailed me and asked where I was going. I told him that I was planning to walk south from Dafni along the coast via the monastery of Simonopetra (where I knew I couldn’t stay, as my fax several weeks earlier requesting to do so had been answered with a polite negative) to Dionysiou (to which a phone call had established that I didn’t need to book, as there would be plenty of space at this time of year). My fellow pilgrim stared at me in astonishment:

“You want to walk? It will take four hours!”

“That’s OK”, I replied, “I like walking.”

“Oh!” he said – “good luck!”, and strode away.

I bought a map from one of the shopkeepers, whose fair-sized store was crammed on the right-hand side with religious books and paraphernalia, and on the left-hand side with booze, and asked him for directions to the track to Simonopetra. He gaped at me too, and said, presumably in the same combi-European tongue as the old lady with the bent finger in Thessaloniki:

“dos oress!”

I figure nobody walks around here then. And there I was thinking this was basically a walking holiday with maybe the odd Orthodox service thrown in. I was about to find out different.

In the event it took less than dos oress to walk to Simonopetra, even with the delay accorded by a group of five large riderless horses, including one apparently alpha male stallion, that blocked the track, eyeing me with suspicion; I approached them step by sidelong step with my hand outstretched and edged past gingerly as they stepped forward to investigate, backing away with the same nervous benediction as I had come with. They took a couple of steps to follow me, then appeared satisfied and contented themselves with staring at my retreating figure. There was plenty of switchback climbing among tumbling forests, scrubby bushland and brooks racing down from high falls; but beyond a certain point it was all downhill until a final short rise at the top of which I rounded a corner, and saw this:

The monastery of Simon Peter, like the church founded by the saint to whom it is dedicated, was built upon a rock. And what a rock.

The monastery of Simon Peter, like the church founded by the saint to whom it is dedicated, was built upon a rock. And what a rock.

Since I was passing, I thought I would look at the church within, and began to climb an arched, covered stone stairway that ascended towards the heart of the monastery. As I was going up, a tall, bespectacled, bare-headed monk, thirty-something with a helpful, scholarly face, plaited brown hair falling onto his neck, and a bushy beard to match, was descending in his black robe; seeing me, he asked in what I took to be German-accented English whether I was looking for the guest house.

“No,” I replied, “I know I can’t stay, you’re full tonight” and told him about the fax.

“Well, you never know, we sometimes have cancellations,” he said; “let me take you down there.”

The guest house master looked me up and down, and said, in fluent English:

“The reason we said no is not because we are full, it’s because we are preparing for our annual festival next week.” (I later figured out that their annual festival was Christmas; although the date was December 30th in the rest of the world, which uses the Gregorian calendar, here on Athos they use the older Julian calendar, which was abandoned everywhere else by the early years of the 20th century, and runs about two weeks behind.) “But since there’s only one of you…”

In the vestibule, lined with aerial views of Agia Sofia (the 6th century Byzantine Emperor Justinian’s giant church in Istanbul – sorry, Constantinople – and the mothership of Orthodoxy) there was a huge guest register, which I was asked to fill out; as I did so, I looked back through several pages, each with several dozen lines, and mine was the only entry in Roman script. While I waited, I was served with a tray on which there stood a large glass of water, a small glass of ouzo, and three rough-hewn slabs of sticky, icing-sugar-coated Turkish delight. Finally, an older monk approached, with a long, thin greying beard, and guided me to my room, a six-bed dorm occupied by one young Greek man languishing under a brown blanket. The monk gestured around the room:

“All these beds are yours,” he quipped.

“And now?” I asked.

“Vespers is at 3.30. It will last maybe an hour. After that, there is a meal. Maybe afterwards, you will have the chance to talk to the monks.”

I went to Vespers, up the stairs I had started on before, round a corner and out onto a wooden balcony attached to the side of the building and hanging with an almost miraculous absence of anxiety above several hundred metres of pure space (you can see it in the photo above if you look between the pink building and the archway to its right). Here I encountered an elderly monk with a long grey beard, a skewed neck, and a twinkle in his eye. He caught me eyeing the sizable bell which hung from a rafter of this balcony, and made a gesture implying that I should ring it.

“Ding ding – hello!” he burst out, and collapsed in laughter.

I was not at all tempted to ring the bell, but stood nervously instead in an open vestibule in front of a locked door, judging that I was in the right place by the presence of the young Greek with whom I was sharing my dorm. Eventually a monk opened it, and I followed them into a small antechamber, hung on either side of the central archway into the church with a couple of large icons. The leading monk and the young Greek crossed themselves profusely in front of each icon, and then bent to kiss its glass before proceeding to the next one, where they performed the same operation. Finding myself overcome with a fret about the sanitary aspects of this, I contented myself with crossing in front of the icons (well, I could remember how to do that) and bowing slightly.

Rather than entering the church itself through the main, central archway, the young Greek had gone through a smaller doorway at the left hand side, and was now slouched next to this doorway in the farthest back of a row of four wood-panelled cubicle-seats that ran along the left-hand wall of the church, behind a low screen separating this rearward section from the apse of the church. As the monks streamed in in their black robes, three other young men in civvies had positioned themselves in the equivalent rearward corner of the church on the right-hand side. Not knowing what to do or where to sit, and having no guidance, I stuffed myself into the second cubicle along the back wall from the left-hand rear corner door, and remained standing. Monks whirled in, moving forward and sideways to cross themselves and kiss the variety of icons on display, before seating themselves in the apses, or in the case of a couple of elderly grey-bearded gents, collapsing into seats in the corner near me, forward of the young Greek layman. At this point, right before the service started, the old monk with the skewed eye strolled up to me and cracked what I took to be a joke, in Greek; since I had no idea what he was saying – was he making fun of me for not ringing the bell? – I had no choice but to raise my hands in the air and shrug. He chuckled deeply and walked away.

The action started with a Kyrie Eleison. Or rather with a kyriekyriekyriekyriekyriekyriekyriekyriekyriekyriekyriekyrieeleison, a kyriekyriekyriekyriekyriekyriekyriekyriekyriekyriekyriekyrieeleison, and then several more kyriekyriekyriekyriekyriekyriekyriekyriekyriekyriekyriekyrieeleisons, delivered at breakneck pace in extended virtuoso performance by a monk in one of the apses. Then the chanting proper began, ages and stages of call and response in plainsong and harmonies from apse to apse, interrupted only by flurries of black-robed monks genuflecting and crossing themselves in front of various icons positioned around the tiny church. Of this particular service I don’t remember a great deal, largely because it was a major stresser, induced by the fact that I didn’t know what the hell I was supposed to be doing. Was I in the right seat, or had I committed some colossal layman’s faux pas and was positioned where some crucial monk-official was supposed to be? When was I supposed to sit, and when to stand? There didn’t seem to be any discernible pattern among either laymen or monks. It just all went on and on and on, for an hour or more (little did I know), until one of the priests strode forward from the sanctuary bearing a metre-wide cake, a shallow cone no more than five centimeters high at its centre and covered with what appeared to be icing sugar. Incense was shaken, he intoned a ritual blessing over it, and then abruptly disappeared, still bearing it, through the main doorway and out of the church. Suddenly, everybody stood up and followed him. I brought up a sheepish rear, finding myself back in the antechamber and standing in a queue, for I knew not what, with the monks in the lead, and behind them the group in civvies.

The line shuffled forward; it turned out that the big cake had been cut, and everybody in their turn was being gifted a crumbly handful in a paper napkin. I bowed, and dutifully took my piece (it later turned out that I shouldn’t have done. This ritual is a gesture of friendship at the end of the service for those who have not taken communion, and since no communion had been offered at this service, everybody received the crumbly cake. However, non-Orthodox, who do not understand the background or meaning of the ritual, are not supposed to participate.) Once in possession of the napkin, it was a few short strides into the dining hall:

http://darkwing.uoregon.edu/~klesh/Athos11/SimonopetraTrap.jpg

http://darkwing.uoregon.edu/~klesh/Athos11/SimonopetraTrap.jpg

Here, amid the splendour of painted saints, I was seated at a table towards the rear, alone apart from the young Greek layman; the monks were seated further forward on the other side, while the plainclothes crowd occupied the table behind them. A spoken blessing served as the starting gun, after which the only sound was the hurried clink of metal cutlery on metal plates. There was bread to be broken, green beans in sauce on one plate and diced onions on another, a tray of fabulously lush and wrinkled black olives, a large metal jug and metal cup for water, and smaller counterparts for red wine. I plunged in, but my technique was inefficient; before I was barely half way full, the cacophony of clinking from around the hall began to subside, and to fade, and then became silence. Not wishing to be the lone clinker, I settled my fork on the table, and waited. A bell rang, and everyone stood.

As the monks were shuffling out, one of the plainclothes approached and told me I should return to my dorm. There was a Chinese monk, he said, Father Isaias, who boarded in the building where the dorm was; he could speak English, and would answer any questions. But back in the dorm, there was only another young man in civvies, who told me that Father Isaias was away. The next service, he said, would be at three in the morning.

At 2.30 in the morning, the young Greek layman’s alarm went off on his mobile. He ignored it. At 3.00, the thunderstorm began, cracking out across the surrounding hills and sending sheets of rain spraying off the balconies. It went on until 4.00, as I drifted serenely in and out of consciousness. At 4.30, the layman arose and left the room. I went back to sleep. At 6.15, I dragged myself out of bed and pulled my clothes on. It was chucking it down as I crossed the courtyard and climbed the steps. The church door was locked; too late.

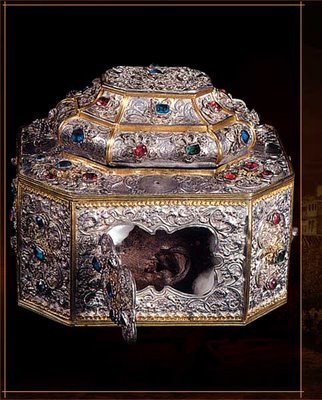

At 9.00 there was another chance. An hour of icon-kissing and black monk flurries, notable for the leading role in chanting taken by a young plainclothes, and this time with a communion at the end. As if to forestall any danger that I might try to take part in this, I suddenly found in front of me Father Isaias, instantly recognizable by his Chinese beard; just like in the old paintings, there was almost nothing on his chin, but long wispy moustaches descended to either side of his mouth. Nothing was said, but I had the feeling that my absence from the service in the middle of the night had been noted. He escorted me to the dining hall, where breakfast was served (or was it lunch? It was exactly the same as last evening’s meal, except that green peas replaced green beans, and there was no wine). This time there were more monks, and there was a reading; the cutlery clinked out more slowly, and there was time to get my fill.

Father Isaias directed me to the place where I would need to wait to get the bus back to Dafni. The bus (in fact a jeep) was driven by a thirty-something Greek monk with baggy black tracksuit trousers beneath his cape, and English good enough that his Greek passengers remarked on it.

“Where did you learn your English?” I asked. “In school?”

“No! They tried to teach me there, but I didn’t learn anything.” He paused, and laughed. “I travelled around. I was searching for something. Did you talk to any of the monks?”

“No, not really. We were supposed to talk to the Chinese monk, Father Isaias, but he wasn’t around last night.”

“He’s not Chinese! Not really, anyway – he’s Swiss. His family are all Buddhists, though. He used to work in banking in Switzerland, making loads of money. But then” – here, he smiled deeply – “well, he found the love of God, and he found his way here.”

“So where do the monks all come from – are they mostly Greek?”

“80% Greek or so, yes. Those who aren’t have to learn Greek – there’s a place in Thessaloniki where they go for six months before they come here. Not that we are saying Greek is a superior language or anything – of course it’s useful because the scriptures are written in Greek, but mostly it’s just that we have to communicate, and that’s the language we speak on the mountain.”

“So what happens after they learn Greek?”

“Well, then they come and live in a particular monastery for a couple of years as novices, and learn how to be a monk. That way they can see if it’s right for them. And if it is, then they stay.”

“So those people in plainclothes, there was one singing in the service with the monks, are they novices? They don’t wear monk’s gear, and they keep shaving, until they are actually ordained as monks?”

“That’s the way we do it at Simonopetra, yes. But every monastery is different. We are one of the most liberal and open, we welcome anyone – that way we believe that people can see for themselves and understand, and make up their minds. But some are much stricter. You are lucky that you came to us!”

“Well, yes, it was luck – I had actually been told by fax I couldn’t stay, and I was on my way to Dionysou.”

“Dionysou!”, he laughed out loud. “They’re really strict! You wouldn’t have liked it there at all!”

“Are you more in touch with the world than most places, then? Do you keep up with what’s going on out there?”

“Well I do, I pretty much keep up with what’s going on. We have a room with an internet connection – most monasteries don’t, but we do. On the other hand, there are some monks even at Simonopetra – you know, I was talking to an old Hungarian monk the other day, and he had never even heard of Osama bin Laden!” He guffawed.

“So how does the monastery run? Do you all have particular specialities?”

“Yes, we all have our own jobs – most have more than one. I clean the paths!” Here he burst out again in melodious laughter. “And I try and persuade them to do sustainable, ecological things – but they don’t listen to me.” He laughed again.

At this moment we pulled in by an array of solar panels by the track. When I pointed them out, he said:

“Oh yes – we have a whole hillside full of them up on the mountain.”

He brought the jeep to a halt, jumped out, and beckoned me to follow him. He led me into a large old building by the roadside, and left me in a small chapel decorated with pictures of the saints for a few minutes; I looked out over the chill grey choppy waters of the Aegean. When he returned, he beckoned to the door, and said:

“Right, that’s it, I’m done.”

We stepped outside, to be greeted by a bent old grey-haired man in dull, tatty clothes. They conversed for a while in Greek; the monk became increasingly agitated, in an apologetic-seeming way, while the old man appeared to be entreating him. At last, the monk waved the old man away, and we walked back to the jeep.

“What was that about?”

He started the engine. “The old man, he wanted money. They get on to the mountain, and often they have no money, no papers, nothing. Many are from what used to be Yugoslavia. Some of them are even Muslims! They come here and want us to give them money.”

“So what do you do?”

“We give them fifteen Euros, and a bed for the night. Then in the morning we tell them to move on. So they move from monastery to monastery. But I don’t have any money, and the monk who normally lives here is not here right now, so what can I do?”

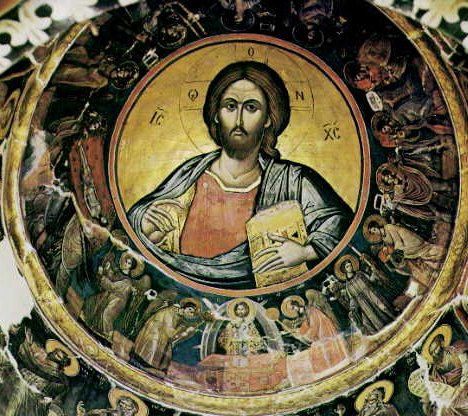

He raised his hand sadly, palm upwards. We drove on, up the mountain, over broken roads, and ascended into fog and rain. We talked of travel and religion; I repeated my observation that Orthodox Christianity seemed less focussed on blood and suffering, and particularly the crucifixion, than the western varieties.

“You figured that out by yourself, without talking to the monks? That’s very good! But that’s right, you know; the crucifixion was important, but it was only a small part of his life!”

As we dropped through the mist into Karyes, the “capital” of Athos (three shops, a post office, a church, a bus stop and a few assorted houses), he turned to me, waved his hand in the air, and said:

“Vatopedi.”

“What?”

“Vatopedi. That’s the monastery you should go to tonight. They are the most liberal of all. They will explain it to you well.”

As we parted in the pouring rain, he recommended that I should read the works of Kallistos Ware.

“He writes very good books about Orthodoxy, in English. He is English, you know! He is from Oxford, Cambridge, one of those places. And we like reading him because he can say bad things about the Byzantine empire. As Greeks, we are not allowed to think anything bad about Byzantium, we are supposed to think it was perfect…”

He guffawed again. I shook his hand. As he loped back to his truck, I thought:

“That is one of the happiest men I have ever met…”